Cooking the Books | Company Hides $150M of Expenses

Why didn’t this public retailer catch a $150M error/fraud?

Today’s Sponsor: Jellyfish

Jellyfish, the go-to source for software engineering intelligence, wants you to never track down time sheets again.

Software capitalization is a requirement for almost all modern businesses today. However, the tedious back-and-forth between engineering and finance doesn’t have to be part of the story. Download the 4 communication best practices for streamlining cost capitalization…and start speaking the same language with ease.

The “F” Word - Fraud

When a single accountant can alter $150M in accounting entries, it raises serious concerns about trust, systems, and internal controls.

Macy’s announced last week it was delaying its quarterly earnings report due to an investigation into the actions of a single accountant who intentionally made erroneous entries to lower expenses by ~$150M over the past 3 years.

Let’s start with defining fraud:

Fraud = any activity that relies on deception in order to achieve a gain. Fraud becomes a crime when it is a knowing misrepresentation of the truth or concealment of a material fact to induce another to act to his/her detriment.

While Macy’s did not use the “F” word (aka “fraud”), if someone is intentionally manipulating financials (against accounting rules) to appear more favorable to investors then that smells like fraud.

The level of fraud at companies (particularly private ones) is much higher than most folks realize, but it is rarely labeled as “fraud”…

Many private companies knowingly report things incorrectly so the metrics that the board/investors care about look better. Eventually, it may get fixed as new accounting leaders come in or auditors discover the issue but that could be many years (if ever). These changes are packaged as an accounting policy change or “we didn’t know” — sometimes true, but often someone knows that accounting is wrong…

Investigating the Fraud

There are two relevant facts that we know about the Macy’s fraud:

Delivery expenses were under reported by ~$150M over the past 3 years

Macy’s cash balance was not impacted

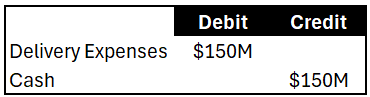

Normally the accounting for delivery expenses would look like the below (expenses goes up and cash goes down). And since Macy’s said cash wasn’t impacted, we know the cash was paid to the vendors.

So the only real way to commit this fraud would be to reduce the delivery expense account and then debit either an asset or liability account, which hides the expense on the balance sheet.

In order for a fraud like this to occur, you have to bury expenses on the balance sheet. I know private companies that have done something like this to a degree (some more intentional than others). Since they are not public companies, it is easier to get away with this because VCs pay less (if any) attention on the balance sheet.

So where is the $150M expenses buried on the balance sheet?

Macy’s said that it identified the issue in “one of its accrual accounts”. There can be accrual accounts in most balance sheet lines below, but for the employee to hide $150M it would need to be in a larger balance account and it would have to be an account that an employee managing delivery expenses also has access to. That leaves two possible balance sheet lines:

Merchandise inventories

Accounts payable & accrued liabilities

Given the size of the company though (and number of accountants at Macy’s) I don’t think this particular employee had enough access to the inventory accounts to hide $150M (at least I hope not), so I suspect the employee was committing the fraud by artificially lowering the delivery expense accrual at the end of each period. Which would mean that the “Accounts payable and accrued liabilities account should be $150M higher.

Fraud Size Matters

Let me start by saying, all fraud is bad….But from an accounting control perspective the size of the fraud and length of time it goes undetected does matter.

I am going to discuss two “common” types of fraud:

Asset misappropriation - When an employee steals or misuses company assets, such as cash, inventory, or equipment

Small asset misappropriation regularly occurs - especially at large companies. A frequent example of this is employees abusing expense reimbursements (getting reimbursed for a family vacation, personal items, etc). I have seen crazy stuff that some people try to expense and they always have a lame excuse on why they did it.

Financial statement fraud - When a company's financial reports are manipulated to deceive investors, often by inflating revenues or hiding expenses.

This is less common than the theft mentioned above, but it is usually much more serious given the typical magnitude and intent of its impact. The $150M Macy's fraud is this kind of fraud.

Stealing stuff (#1 above) is usually on a smaller scale because the theft directly benefits the employee. While financial statement fraud is usually a much larger dollar amount because it has to be larger to make a significant financial statement impact. For example, an employee might steal $5,000 worth of equipment, but $5,000 is not going to do anything to impact investor decisions. When financial statements are wrong by a few thousand dollars it is probably just an error or deemed immaterial (not intentional fraud to deceive investors) — even if it is a known error, it is too small to matter.

Is the $150M Macy’s fraud big considering its total revenue?

Some people have argued that the $150M is only ~3% of the total delivery expenses over the same period of time. That seems pretty small, right?

BUT….if you look at it compared to net income then it could be very significant. Macy’s revenue has been declining and because of some restructuring charges in 2023, net income was only $105M in 2023. So the $150M of hidden expenses could make up something like 50% of 2023 profits….

Further, the delivery expenses and contribution margins (which would include delivery expenses) is a closely watched metric for investors of retailers like Macy’s. Fraud more commonly occurs in areas they impact key metrics.

Cloud companies: For cloud companies instead of delivery expenses, a manipulated metric I often see is gross margins. Gross margins is a carefully tracked metric by investors so companies try hard to keep expenses out of it. While there is some grey on what gets included, other things are very clear. I have personally seen accounting teams told to put something outside of COGS that should clearly be included because it would be bad for gross margins.

Fraud Triangle

Once you cross the integrity line it is a very slippery slope. The thing with accounting fraud though is that the tricks, errors, or flat out fraud always catch up to you eventually….

If the company is growing quickly then fraud is easier to hide. But when growth slows (and it always eventually does), then that is when the fraud comes to light.

In accounting classes they teach you about the “fraud triangle”. There are three things that are present when fraud occurs:

Pressure - motivation/incentive to commit fraud

Rationalization - person’s justification of why it is OK

Opportunity - knowledge and ability to commit the fraud

1. Pressure - why the employee did it?

Based on what we know, it doesn’t appear that the employee directly benefited from hiding the $150M expenses (i.e. didn’t directly steal any money). There are a few theories on why the employee did it:

They potentially received indirect benefits from the company hitting certain profit targets (i.e. company/department bonus that pays out for certain metrics) or from the stock price performing better as a result. However…given the presumed level of this employee I would guess that their indirect benefit would be pretty small. It’s hard for me to imagine the benefit being large enough for them to justify committing fraud. If this employee did have a large incentive tied to the delivery expense number, then that is a major problem with incentives.

They felt pressure from management to push the accounting rules a bit to make delivery expenses look better (after all, we are only talking about ~1% of delivery expenses per year. It is tiny, right?)

It started as an error and snowballed. The employee made an honest mistake originally but then tried to hide it because it would have been really bad to take the hit once it was discovered.

If I was a betting man, I would guess it was either #2 or #3 in this case. Only way I think it is #1 is if this employee also had some insider trading operation going on as well…

2. Rationalization

People rationalize fraud for a variety of reasons. It usually doesn’t start as actually rationalizing fraud though, but rather simply rationalizing a grey area. Given the right reasons though, lots of people can be convinced that something is OK.

“It’s a very small amount of total expenses”

“The accounting is bit grey. Some people probably do it like this”

“It’s just temporary and we will recognize the expense later”

“Management told me to do it so it is probably fine”

“No one is getting hurt. It’s just some accounting changes”

3. Opportunity

This is the most alarming, but also not surprising, aspect of fraud like the one at Macy’s.

Macy’s blamed a “single employee” as being responsible. Every journal entry in accounting should be reviewed at least by one other person though. Where is this person’s manager? Why didn’t they catch it? That employee’s leadership all the way up to the CFO of Macy’s is sweating a little bit right now.

Why didn’t the auditors catch the error? People outside of accounting (and those who haven’t been an auditor) give them way too much credit for their ability to find stuff like this. I promise that many Big 4 audit teams have missed something like this. Either way, their auditor (KPMG) is also sweating right now because they theoretically should have caught such a large issue.

Lack of internal controls. Were there no internal inspections of the delivery expenses? Or other controls that would have caught the fraud?

Low-risk accounts get less scrutiny. If you want to commit fraud…do it in a low-risk and large account because a lot less time is spent reviewing those accounts.

Why didn’t internal reviews of delivery expenses catch it? Companies perform lots of analytics around account trends which is reviewed throughout the company. Delivery costs and volume of deliveries changed a lot over the past 3 years changed as a result of COVID and other factors so this large change helped disguise the fraud.

Final Thoughts

99%+ of people don’t wake up and decide to commit fraud. It is easy to justify fraud though as you tiptoe more and more into the grey.

But the thing with financial statement fraud is that it always catches up to you. In Macy’s case, the under expensing would have to continually increase in order to get the financial results you want. When growth slows though it becomes increasingly difficult to hide.

And the even bigger problem is that if you are hiding something like this then the company is probably not fixing the underlying problem that would make your business better in the long term. Had Macy’s management known its delivery expenses were actually higher by $150M they may have done something different.

Make sure you have sufficient controls and experienced people in place to prevent this type of fraud.

*A future OnlyCFO webinar series will cover financial controls and ensuring accurate financial statements…Sign up to be included.

Footnotes:

Download the 4 communication best practices for streamlining cost capitalization (today’s sponsor)

Sign up for the OnlyCFO webinar series! Our first webinar is on how your annual planning might break in 2025.

Send an email to onlycfo@onlycfo.io if you want to be a sponsor of the OnlyCFO newsletter or my new webinar series. Get in front of 28K+ finance/accounting professionals

Check out OnlyExperts to find offshore accounting resources. They have some amazing talent for 20% the cost of a U.S. hire.

Fraud can seem abstract, but this article makes it tangible with clear examples and sharp insights. From the fraud triangle to Macy’s systemic gaps, it’s a practical and valuable breakdown of what went wrong.

Excellent analysis from an outside observer!