Dangers of SaaS Metrics | What NOT to do

Misunderstanding and misuse of SaaS metrics can sneakily kill a company.

Today’s Sponsor: NetSuite

Wondering what CFOs should prioritize and consider in 2024? Download your guide.

We asked the top finance minds what they think. AI is a theme, team empowerment and sharpening your forecasting skills are just as critical.

A discounted cash flow (DCF) is theoretically a perfect way to value a company because ultimately a company should be worth their future cash flows.

But DCFs are ALWAYS very wrong because of:

The large number of assumptions required

The time horizon used to value a company (the entire life of the company).

Given the long time horizon in a DCF all the assumptions will be wildly wrong over the long-term.

BUT….DCFs are not useless. DCFs should be used as a mental model for how to value and increase the value of a company.

Used as a framework for making business decisions and investments, the understanding of a DCF is very valuable. Many software company founders and leaders clearly don’t understand DCFs and what drives long-term business value though.

Too many VC-backed software company leaders become myopically focused on reaching some perceived milestone of success that will have venture capitalists begging to give them money.

“We must hit $10m in ARR and then we can raise a Series B!”

“We must be growing X% and then the Series C will be easy”

“Our Rule of 40 score must be X and then….”

Too much money can make people stupid and it is only when money is running out that they actually start thinking about what makes a business valuable and not focused on what they think investors want.

Having short-term goals is great, but many folks end up losing the forest for the trees. Success doesn’t come from focusing on a single metric but rather how it can maximize value by creating the most cash flow over the life of the company.

Many companies end up focusing on a specific metric/milestone and believe their business is healthy once it is “good” so they should therefore step on the accelerator and grow faster.

But so many people misinterpret SaaS metrics and don’t understand how they fit into the broader picture of building a successful business.

Deceiving SaaS Metrics

Let’s look at an example of misunderstanding and flaws of a SaaS metric by looking at the LTV/CAC ratio.

Similar to a DCF, the LTV/CAC ratio is theoretically perfect because it should tell you the cash flow generation from a single customer (like a DCF but at an individual customer level).

A higher LTV/CAC ratio means for every dollar of sales and marketing, the company has higher profits and better unit economics.

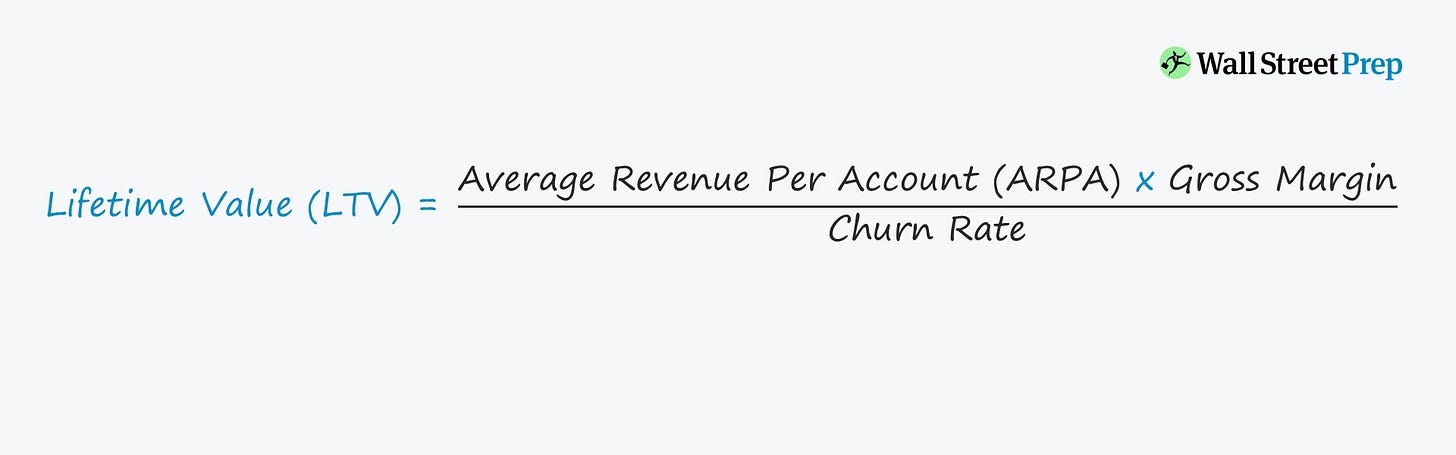

LTV = “lifetime value” of a customer

LTV is the lifetime profit stream of a customer. It is typically calculated as seen below (but there are several other iterations).

CAC = customer acquisition cost

CAC is calculated by taking all sales & marketing costs to acquire a customer

While in theory it is a perfect metric to help drive the right business decisions, it is frequently misused and abused in application. Here are a couple of big mistakes I see:

The biggest and most fatal mistake is not understanding that the LTV/CAC inputs are interdependent and can change significantly during different phases of the business. A couple of examples below:

↑ in ARPA likely results in an ↑ in churn rate. While LTV theoretically increases if you have a higher sales price, you need to account for the increase in churn rate that will come from higher prices which decreases the lifetime value

↑ in sales growth likely means an increase in CAC, which decreases the LTV/CAC ratio. This can happen for a lot of reasons, but much higher sales growth often means lower sales efficiency.

The other common fatal mistake is believing that (1 / churn rate) is how long your customers will stick around in the future.

Unless you have been selling for a few years past your calculated customer lifetime then it is just a guess (and probably too long).

Example: If you have been selling your software for 3 years but are calculating a customer lifetime of 15 years then you are almost definitely wrong….You are better off using a more conservative number based on realistic expectations.

And even if you have more churn data, is that what you should expect in the future? Will there more competitors? Are you raising prices? Is there macro environment changes?

As Dave Kellogg (blogger and SaaS guru) has talked about a lot, investors love compound metrics because they are trying to make quick decisions about a business. But compound metrics are a lot less useful for operators because there are so many variables. The LTV/CAC ratio is a big compound metric with some major assumptions.

Concluding Thoughts

Don’t lose the forest for the trees.

A DCF perfectly represents the value of a business and the levers that can be pulled to increase a company’s valuation. While DCFs are always wrong, the framing and mental model of them is critical.

When leaders narrowly focus on specific metrics or milestones, they can become blinded by the metrics outputs and benchmarks.

Companies run out of money all the time with theoretically good LTV/CAC ratios.

All companies that go out of business do so for the same reason – they run out of money. —Don Valentine

Footnotes:

Become a paid subscriber and join the OnlyCFO Community! Discount ends tomorrow (March 9th)!!!

Ask questions and get support from other finance leaders in the software industry. And much more….

Check out NetSuite’s guide on CFO ideas and priorities for 2024

Sponsor OnlyCFO Newsletter and reach 17k+ CFOs, CEO, and other leaders in the software industry.