How to Trick Investors & VCs

Understanding finance tricks in metrics and reporting

If you are new here, then you should know that I talk almost exclusively about software companies, so the lessons below are mostly to help software folks commit fraud and trick investors. If you are hoping to commit fraud in another industry then I am sure there is a blog for that.

Wait…So is this really about how to commit fraud? No. Not really at least.

Some folks try to “honestly” deceive investors with accounting shenanigans, some operators are themselves misled because they don’t understand the basics of accounting/finance, and other people just want to commit straight-up fraud (👋 FTX). The purpose of this post is not to educate you on how to commit/detect fraud, but to help you understand some of the accounting/finance nuances that might deceive investors.

GAAP Lies

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (“GAAP”) are the rules for how companies should do their accounting and external financial reporting (called IFRS outside the U.S.). The problem that can arise from GAAP financials are:

GAAP doesn’t always represent things the way people expect or in a way that most accurately depicts the financial impact.

Even with all the rules, there is still diversity in application.

GAAP can be manipulated to the company’s benefit.

1. Capitalization of Commissions

What does “capitalized commissions” mean?

Until recent years, most SaaS companies expensed sales commissions in the period they were earned by the sales reps - i.e. the AE earns $10K in January then a $10K expense would show up within sales & marketing on the income statement.

Under new accounting rules though, most sales commissions (90%+ of all commissions) for SaaS companies get capitalized on the balance sheet and then expensed over time. The expense is typically recognized over 3 - 5 years. See some public company policies in the first column below.

How can this be deceiving to investors?

Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is calculated by taking all sales & marking (S&M) costs, including commissions, that it takes to obtain new ARR. But if commissions aren’t expensed at the time new ARR is obtained, then those S&M costs will not fully account for all costs to close a deal.

If a company is growing fast, then looking only at GAAP financials can mislead investors on the true CAC, payback period, and general efficiencies because the commissions on the progressively higher ARR get expensed later.

Example: In the example below, I assume all new ARR is created on the very last day of each year. So in year 1, $5 of new ARR is created and there is $1 of commissions earned. Under GAAP, the entire $1 would be capitalized and not expensed in year 1 (except maybe for a very tiny amount). The expense would happen over the next 3 years. As you can see in the last line on the image below, the difference between what commissions are earned vs GAAP expense grows as the company grows ARR faster.

Like most misleading metrics though, it gets exposed once growth slows. As growth slows there is substantially less new ARR, but GAAP commissions remain elevated because all of the previously high commission amounts are still being expensed.

2. Capitalization of Internal-Use Software

There is a GAAP requirement to “capitalize” certain expenses on the balance sheet and expense them over time (vs expensing immediately). The concept is identical to the capitalized commissions topic above.

For SaaS companies, these are R&D costs that go into the development of net new functionality of the SaaS solution being sold. This description may make it sound like a lot gets capitalized, but it actually shouldn’t be that much. There is accounting guidance and standard practices that have developed around how much should be capitalized, but it is a judgemental/grey area. One of my favorite quotes from a Big 4 auditing partner was on this topic:

We want you to capitalize something because the rules require it, but we don’t want you capitalizing too much because it’s less conservative (since it delays more expense).

Leaves a lot of room for “judgment”….

Why can this be deceiving to investors?

There are some pros and cons to capitalizing lots of R&D costs.

Pro: Overall efficiency looks better. Operating Income, EBITDA, etc are higher when a company is growing because more costs are put on the balance sheet and not expensed until later. If a company has not been growing for several years, then there will not be much of an impact because the old stuff that is being expensed now is equal to the new stuff being capitalized and not being expensed.

Con: The amortization of internal-use software gets expensed into COGS (impacting gross margins). Whether it makes sense to you or not…when these costs get expensed at a later date they go to COGS and not R&D. So the reaction of most CFOs is to minimize the amount of capitalized internal-use software because they want to protect gross margins.

Gross margins are highly scrutinized given its impact on the long-term profit potential of a company (you don’t get leverage in the gross margin as you do with R&D, S&M, and G&A).

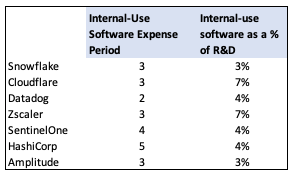

Public software companies generally stay within a fairly tight band. They generally expense internal-use software over 3 to 5 years and it is usually around 5% of all R&D costs. But as you can see below there are some variations that can have a material impact in comparison. What if Hashicorp amortized costs over 2 years like Datadog instead of 5?

Things can vary even more with private companies before they are in the public eye…I have heard of some widely different numbers amongst private companies. Some folks are capitalizing 15-20% of R&D! Overall efficiency probably looks great…But I am guessing GAAP gross margins kind of suck.

3. Stock-Based Compensation (SBC)

Most of the discussions on SBC recently have focused on SBC expense as a % of revenue, but this is only indirectly correlated to the problem of SBC.

The real focus should be on the dilution caused by employee equity awards, not the GAAP expense.

Read the thread below for additional detail, but here is a quick TLDR:

Given the significant drop in software company stock prices, there is an opportunity to lower SBC as a % of revenue based on the accounting rules, while share dilution actually increases. Management will cheer that SBC is coming down…but make sure to look at the dilution impact because that’s all that matters.

VCs are actually pretty good at navigating this because they manage the stock option pool to ensure that they don’t get diluted too much. VCs should, however, pay attention more to equity %s given to various employees…lots of first time founders give away too much to the wrong people and burn through stock option pools too fast.

Categorization of Expenses

GAAP defines how a lot of things should be accounted for, but not everything is black and white. There is a sufficient amount of judgment and diversity in practice that can make certain financial benchmarks much less meaningful (particularly when companies are on the smaller end).

1. Customer Success

The customer success org, particularly customer success management, is frequently debated on which expense line the department belongs to:

Cost of Sales (COGS): If costs live in COGS then they impact gross margins. As discussed above, gross margins are usually pretty protected given its impact.

Sales & Marketing (S&M): While some level of S&M is required to maintain customers, as a company scales and growth slows, S&M as a % of revenue should decline significantly.

For my quick analysis of how companies *should* think about bucketing customer success see the below Twitter thread. But I promise there will never be uniformity on this one.

When comparing to benchmarks, you need to understand where customer success costs are going to make the comparisons more meaningful.

2. Recruiting

Some folks put this to G&A and some allocate these expenses across the company based on headcount.

Zuora, for example, puts it into G&A. But lots of other companies allocate it across the entire company since recruiters are servicing every department.

If a company has a large recruiting team and is putting all costs to G&A while the benchmarks they are comparing to allocate recruiting across all expense lines, then G&A may look bad but gross margins, R&D, and S&M will all look pretty good.

3. G&A Dumping Ground

This is almost exclusively an early-stage company trick (or just bad accounting) since an audit should generally catch it. While there is some judgment in what operating expense line things can be coded, there are some obvious things that don’t belong in G&A. Some things clearly belong in another expense line or they should be allocated across the expense lines because the entire company benefits from it.

Company offsites or events

Facilities, utilities, internet, etc

General software used across the company

I have seen lots of other interesting things get dumped into G&A

Other Tips & Tricks to Deceive Investors

Most of the below items pertain to privately held companies.

VCs are smart people, but they are often easier to trick (especially at the earlier stages) than public market investors for a few reasons:

Company management controls the narrative and what is reported to VCs. Definitions can be loose and changed because they aren’t in the public eye.

Lots of VCs today don’t have a finance background. Many are founders and operators turned VC who don’t have deep accounting/finance knowledge.

Many VCs don’t dig that deep. The focus is on the topline and they assume that everything else will work itself out.

1. Bury the balance sheet

As mentioned above with capitalized commission and internal-use software, the income statement can be manipulated. Lots of board members only really look at the income statement and cash balances. But the full balance sheet holds the keys to potential accounting shenanigans.

If a company doesn’t show the full balance sheet then that’s a red flag. Get the balance sheet and understand how it might be impacting the income statement and SaaS metrics.

2. Create an efficient operating plan by neglecting the following years

This is a classic trick and a personal favorite :). I bet lots of companies did this to some degree this year given the pressure to be more efficient.

For high-growth companies there is a need to continue to hire within sales and marketing to continue the growth trajectory, otherwise, growth will fall flat pretty fast. Sales reps and other GTM teams can take up to 6 months to be ramped and productive. This means that companies need to hire GTM folks in the second half of the year which won’t add to sales in the current year, but only help drive sales in the following year.

So if there is a lot of pressure to be efficient this year, just don’t plan on hiring any of these folks in the financial plan. Boom - efficient! Just don’t tell them that your growth rate will fall from 75% to 20% next year 🤣

The financial plan should show a top-down plan for the following year so this trickery doesn’t happen. At the very least, companies should explain what the implied growth rates would be for the following year.

3. Aggressively Manage Cash

All companies manage cash, but with a focus on efficiency and a lot of investor attention on the “burn multiple” we might see folks be more aggressive.

Burn Multiple = Cash Burn / Net New ARR

The point of the burn multiple is to show how much cash is burned for every $1 of new ARR. A lot of focus has been put on this metric recently amongst high-growth SaaS companies because it is generally a good indicator of overall company efficiency.

If things are looking bad toward the end of the period, just stop paying your bills and get *really* aggressive on collections from your customers. You might piss off a few folks, but your cash burn this period will look great! As for the next period….might be tough since this is a hard trick to pull off consistently. But you may keep your job a little bit longer :)

Again, mostly joking here, but these games are somewhat stupid. Yes, in general companies want to maximize their cash position by collecting faster and paying later, but if a company pushes this hard one period to hit a board number then 1) you may make customers and vendors angry and 2) you can’t play the game forever.

This is another reason why VCs/Boards need to be carefully looking at the balance sheet. Don’t cheer the management team for achieving an amazing burn multiple if the accounts payable balance increased 5x.

4. Non-Standard ARR definition

VC-backed SaaS companies use ARR as their North Star metric because it is more of a leading indicator than GAAP revenue. Management and VCs focus a lot on it, but ARR is not a GAAP metric that has a standard definition. It was developed by the SaaS community and there are lots of different versions of how to define it out there.

I had a good laugh when I saw the below tweet…

Maybe a new term is needed- ARR(ish)

Some other great tricks include:

Use the contractual exit ARR as “ARR”

Remove “one-time” discounts in what you report as ARR

Count professional services as ARR

5. Early-Stage Companies

I never really trust the financials of a company before they have a real controller and are getting their financial statements audited. Often this is somewhere before $15M in ARR but is dependent on the company and when they bring on their first strong accounting hire.

This is usually not the case of anyone actually trying to deceive, but sometimes that accidentally happens. The company is using an outsourced accountant who isn’t that strong or they brought an accountant on full-time who doesn’t know all the complexities.

If you are early-stage SaaS and looking for an accounting firm, send me an email - onlyrealcfo@gmail.com

Concluding Thoughts

This post isn’t an exhaustive list of all the ways investors can be tricked and manipulated, but I hope I accomplished at least the following:

Educate non-finance operators a bit so they themselves won’t be misled in the future

Shame finance leaders who think (or maybe actually are) tricking their investors/board/VCs.

Push investors/VCs to ask more questions, understand how the income statement and balance sheet work together, and call out their portfolio companies that aren’t sharing all the applicable context.

Here are some of my relevant posts that can help further understand this stuff:

How to Read an Income Statement

This is an absolute masterclass

Masterpiece.

H/t for spotting the dynamic of the sales commission capitalisation months ahead of general awareness.