Lies of Stock-Based Compensation (SBC)

SBC expense accounting may not reflect the true financial impact

Stock-based compensation (SBC) is a sneaky destroyer of shareholder returns.

SBC is an important tool when used appropriately but can also be incredibly destructive to shareholder returns when it gets out of control.

SBC is frequently ignored when valuing companies, but it has come back in focus as tech company valuations have fallen from their 2021 highs and their SBC levels (and related shareholder dilution) are at historically high levels.

There are two primary ways investors can evaluate the impact of stock-based compensation:

SBC expense recorded on the income statement

Shareholder dilution caused by SBC

#1 is often used because it is easy to obtain and compare to other companies. But SBC expense can be a very misleading indicator of what actually matters, which is shareholder dilution. If you understand how SBC expensing works then you will understand the pitfalls and may be able to make better decisions using SBC expense.

In this post I will cover what SBC is and how SBC expense can be misleading. In my next post, I will write about potentially better ways to analyze the impact of SBC.

What is SBC?

SBC is equity awards provided to employees or others (e.g. board members, contractors, advisors). Typically these equity awards vest (they are earned) over some period of time and/or as a result of some other requirement — such as reaching a specific stock price or hitting some company milestone.

By far the most common vesting criteria for tech companies is a time-based employee service only condition with a 4 year vesting schedule (1 year cliff and monthly/quarterly vesting after that).

Example: A stock option for 10,000 shares with a 1 year cliff and monthly vesting thereafter

2,500 shares would vest after the employee reaches their one year anniversary and then 208 would vest each month for the next 36 months.

Primary types of awards:

Stock options

Employees are given the right to purchase shares at the grant date fair value of the stock once their options vest.

Restricted Stock Units (RSU)

Employees are granted a number of RSUs and receive the stock upon vesting without having to do anything (no purchase needed)

Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP)

Company program where employees can purchase stock through deductions from their payroll at a discount to the current price (up to a 15% discount). Most ESPPs have a look-back provision which allows the employee to purchase the stock at the lower of the current price or the price from the start of the offer period. This is typically only for public companies.

A key difference between stock options and RSUs is that RSUs will always have value and create shareholder dilution if they vest because they always have value to the employee since the employee doesn’t have to pay anything to get the stock. Stock options require a payment to own the shares so if the stock price is lower than their exercise price (price they must pay to purchase the shares) then they are “underwater” and typically won’t be exercised. For public companies, underwater stock options would never be exercised, but private company stock options might be exercised even though they are underwater because there isn’t an active market, and the stock option holder may believe the price is undervalued.

Stock options are the typical equity award for early stage companies as there is still a ton of upside potential — ability for the stock to go much higher than the exercise price. Once a private company becomes highly valued and nearing an IPO then RSUs might start being granted because the allure of upside potential with stock options is lower. Once public, RSUs are the most common form of equity grants.

RSUs vs Stock Options

If RSUs have no exercise price and are always valuable to the employee then wouldn’t everyone just want RSUs?

It’s not that simple.

Companies don’t provide the same number of stock options as they would RSUs to employees since RSUs have guaranteed value (assuming a company is/goes public) while stock options can be worthless if the stock price doesn’t go up.

If there is a lot of upside in stock price then the stock options end up having more value because you have more of them, which therefore causes more dilution to shareholders. If the stock price falls, is flat, or only increases slightly then RSUs are more valuable. RSUs guarantees shareholder dilution while stock options are only potentially dilutive but have the potential to be much more dilutive.

Private Company Issues with RSUs

RSUs are subject to income tax when they vest versus stock options are generally only taxed once exercised so the tax impact is more in the employee’s control for stock options. Because of this tax issue private companies that grant RSUs almost always add a double vesting trigger:

Time-based vesting like mentioned above (i.e. 4 years of service)

Liquidity event like an IPO or acquisition

The liquidity event condition is added to prevent vesting when the company is private so employees don’t get stuck with a large tax bill that they can’t afford because there is no market to sell their shares.

An issue though is that these double trigger RSUs typically must expire within 5-7 (due to IRS rules that are too boring to explain) while stock options typically have a life of 10 years. There were a lot of companies that previously thought an IPO was ~12-18 months away so they started granting RSUs but now we haven’t seen a software IPO in 2 years! Many of these companies are coming up on the expiration of those RSUs…

Example: Stripe began offering RSUs with double triggers to employees in 2016 with a 7 year expiration. These RSUs started to expire this year. Since the IPO window is shut and Stripe didn’t know when they would be able to IPO they decided to raise funding to modify these employees awards to remove the IPO condition and to provide liquidity (i.e. allow them to sell their shares).

Not all companies can or will do this, so it was a very generous action by Stripe.

Private companies with these types of RSUs don’t record any SBC expense until the IPO actually happens and then there is a large catch up of expense, which makes SBC expense lumpy.

How does SBC expense work?

Accounting rules require companies to recognize an expense from equity awards on their income statement - categorized based on the people receiving the awards. Income statements may include a footnote that break out how much SBC expense is in each line (like the one below from Snowflake).

How this expense is recognized on the income statement can be confusing and lead people to make the wrong conclusions. This is a very nuanced and complicated topic so I am just discussing the main things to be aware of. Two main concepts when determining how to expense SBC are:

Fair value of the award

Timing of expense

Fair Value

The fair value of an equity award is almost always determined on the grant date (i.e. the date the board approves it) and is NOT subsequently changed.

The fair value of the typical RSU is just the price of the stock on the date of the grant.

Calculating the fair value of stock options is a bit more complicated since employees are just given the right to purchase the stock. Most companies will use the Black-Scholes model to determine the fair value of stock options. The Black-Scholes pricing model uses various inputs to estimate the fair value. A required financial disclosure is the average grant date fair value of stock options, so you can look at a company’s financials and see how stock options are being expensed.

Timing of Expense

The vast majority of equity awards are recognized over the required service period which for the majority of tech companies is 4 years (i.e. equity awards “vest” over 4 years) but there are three types of vesting conditions:

Service - as time passes vesting occurs (most common)

Performance - some milestone or target must be achieved

Market - vesting occurs based on stock price or valuation targets

For awards with only a service condition, companies have a choice on how they expense the award:

Accelerated expensing (graded vesting method)

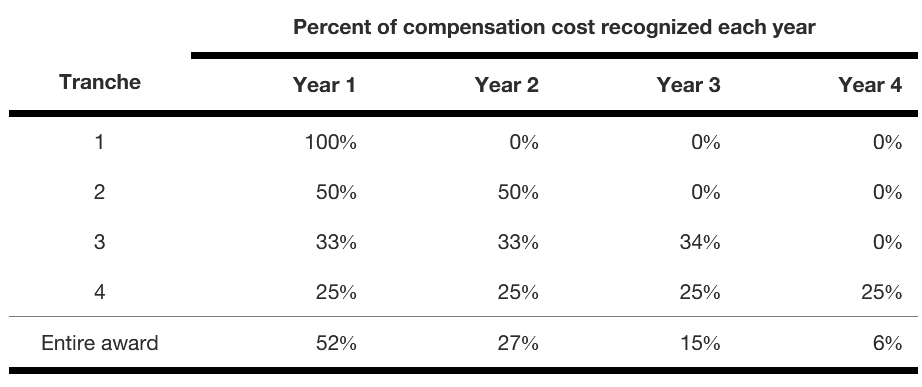

Almost all equity grants vest in tranches. A typical tech company grant has 37 tranches — one at the one year cliff and then 36 more tranches each month over the next three years (4 years of total vesting). Under accelerated expensing, each of these 37 tranches are expensed from the grant date to each of their respective vesting end dates. The simple example below of just 4 tranches over 4 years shows how much this accelerates expense — almost 80% of the expense occurs in the first 2 years!

Straight-line method

This is the more common method. The expense is recognized evenly between the grant date and the last vest date. In the typical 4 year vesting period this means the total expense would be spread across 4 years (25% each year).

The difference between the accelerated method and straight-line can cause some big temporary differences in SBC, but the total expense will eventually be the same either way.

For awards granted with performance or market conditions then the accelerated method MUST be used. Again, if a company has a lot of these then the timing of SBC expense can look significantly different between companies.

Non-GAAP Metrics

GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles) refers to the set of rules that govern how a company should do its accounting and report its financials. But companies want to present different information which they feel more accurately reflects the economics of their business. SBC is the most common adjustment which can be really deceiving regarding investor return potential.

Two favorite non-GAAP metrics for software companies are:

Free Cash Flow (FCF)

FCF = Cash from operations - Fixed asset purchases - Capitalized software

The idea with FCF is that it represents the cash generated/used from normal operations of the business so it is an indicator of profitability and liquidity of the company.

The “trick” here is FCF will look much better than GAAP net income because it excludes SBC since SBC doesn’t directly involve cash. The other differences between FCF and net income are mostly timing differences and even out overtime. SBC though is a permanent difference because no cash changes hands between the company and the employees at any point.

Many people try to bake in the negative impact of SBC by reducing FCF by SBC, but SBC expense is often not a good indicator of the dilution impact (more on this below).

Non-GAAP net income

Below is Snowflake’s recent Q1 reconciliation between the GAAP net loss and the non-GAAP net income that they presented. *Note - anytime a non-GAAP financial number is presented the company is required to reconcile to the GAAP equivalent.

As you can see the SBC charge of $288M being added back, which is 46% of revenue, is how Snowflake was able to report “non-GAAP net income”.

SBC Expense is Deceiving

Now I have covered the basics of how SBC expensing works it may start to make sense how SBC expense can be deceiving. Below are some of the bigger ways SBC can deceive shareholders.

Stock price volatility can make SBC expense incomparable

Remember that SBC expense is based on the grant date fair value and that price is fixed for the duration of the award (typically 4 years).

Let’s look at an example of two hypothetical companies:

Company 1 went public in January 2021 and had an astronomically high valuation and stock price. The company then doubled its workforce by the end of 2021 while the stock price continued to skyrocket. All of those employees got equity at these high prices. But…the stock price subsequently crashed over the next 6 months.

Company 2 is basically identical to Company 1 except it went public a year later at 20% the valuation of Company 1 because of the downturn in the market. Company 2 also doubled headcount growth over the next 12 months when the stock price was 20% of Company 1.

Company 1 and Company 2 could be identical but Company 1 would have significantly more SBC expense as a result of the stock price volatility of when these two companies grew headcount. Because the fair value of an award is locked at the date of grant companies may be “stuck” with that expense over the entire vesting period (i.e. 4 years from grant).

In fact…Company 2 likely had to issue even more equity than Company 1 to provide employee equity packages that are pegged to a $ amount, which creates even more dilution. So Company 2 might create similar SBC expense as Company 1 but then have WAY more dilution.

A caveat here is that Company 1 might be pressured to also issue more awards to existing employees because everyone’s RSUs are now worth 20% of what they were before. This is one serious problem with SBC that I discuss more below.

Stock options can have a very different dilution impact than RSUs even when SBC expense is similar.

When stock prices are continually going up then companies that give more stock options may have a more dilutive impact because more stock options are given relative to RSUs. But when stock prices fall then stock options will be under water and won’t add to dilution at all. While RSUs will always add to dilution.

Further, if stock options vest but are never exercised the expense is not reversed even though there is no dilution. Stock options may go unexercised because they are underwater or because there is no liquid market for them in the case of private companies. This generally wouldn’t apply to RSUs.

Accounting rules allow companies to account for “forfeitures” by either 1) estimating forfeitures or 2) as forfeitures actually occur.

Forfeiture = unvested stock option that expires (typically because the employee terminates)

SBC expense recorded on the financials from awards that are later forfeited is reversed. This means if an employee has a stock option that has a 1 one year cliff (i.e. no equity is earned until 12 months of employment) and they quit after 11 months then any expense recognized with that stock option should be reversed out. Companies can either estimate how much of this SBC expense reversing will happen or just reverse out the entire expense when it occurs.

For executives with large grants this difference in accounting could have a material timing impact and make SBC expense lumpy.

But remember, if an award vests, then the SBC expense is not reversed even if the award is not exercised (which may be the case in underwater stock options).

Accounting rules allow SBC expense to be recognized under two different methods.

As discussed above, the difference between the below two methods on SBC expense can be dramatic. When comparing two different companies that are growing fast but use different SBC expensing methods there can be material differences in SBC expense. Investors relying on SBC should understand the accounting policies.

Straight-line over the vesting period (typically 4 years)

Accelerated method which has the effect of recognizing a lot more expense in the first 2 years.

Market condition awards are expensed even if the vesting conditions are not met.

Market condition awards is an exception to an early statement that the SBC expense related forfeitures (awards that don’t vest) is reversed.

A market condition is typically an award that only vests if the valuation of the company (or stock price) reaches a certain level. These are most commonly awarded to the CEO but could be other executives as well. Unlike other equity awards where the expense is reversed if it doesn’t vest, market condition awards are never reversed even though they do not create shareholder dilution.

Market-Based RSU Example:

In March 2021, the CEO and CFO of SentinelOne were granted stock options with a market condition of undisclosed share price targets. They recorded $3.6M of SBC expense related to these awards in their most recent fiscal year and they have $12.7M in unrecognized expense that will be recorded on the income statement over the next 3.5 years.

This expense will hit SentinelOne’s income statement regardless if the shares vest or not because that is how marked-based awards are treated (based on the accounting rules). While we don’t know the stock price targets, the awards were given at near the peak of the market in 2021 and SentinelOne’s stock price has cratered since then….so there is a strong possibility that these awards don’t vest and no dilution results.

But just looking at the SBC expense may tell a different story.

Many public companies treat SBC the same as cash so making lots of non-GAAP adjustments to remove SBC is deceiving.

There are indicators that public companies treat SBC the same as cash. Employees participate on the upside but don’t share much risk on the downside.

Equity is given to employees pegged to a $ amount

Additional equity grants are often given if the stock price falls in order to make employees whole from a $ perspective

Vast majority of employees sell RSUs immediately after vesting.

Concluding Thoughts

The purpose of this post is to show you how SBC expense can be deceiving with all the confusing was SBC expensing works. SBC expense is an indirect indicator of what actually matters, shareholder dilution, and often it’s a bad indicator. SBC expensing is governed by accounting rules that can make the amount of expense wildly inconsistent across companies. This is especially true in times of high stock price volatility.

Ultimately what matters is the shareholder dilution caused by the SBC. In my next post I will cover how to look at shareholder dilution and other ways to understand the impact of SBC.

Reading 📚

Stock-Based Compensation by Morgan Stanely

Unraveling Stock-Based Compensation by Next Big Teng

PwC Stock-Based Compensation Guide - for those with a lot of free time…

Always love your posts my friend. I know you’ll be getting to this on your next post --- a recommendation to look at dilution as the better way to evaluate/adjust FCF.

In other words, why penalize companies with this artificial SBC expense that often has no relationship to the current true cost of those RSUs and stock options? -- since they are costed out based in the timing of an IPO, for example. And I agree in principal -- the dilutive effect is more meaningful.

But the problem with that is that you’re comparing two different things -- 1) FCF in a period, and 2) the total dilutive effect over time of the employee shares whose cost never hit FCF (and never will) even though the costs are real to all shareholders.

It seems to me that the best way to truly understand the “cost” of the stock-based compensation is to “ price” the dilution at today’s stock price value and amortize it -- over some reasonable period of time reflecting how those employee shares vest. A kind of repricing of thirst SBC expense based on current values (rather than say the IPO value).

But maybe I’m stealing your thunder?

Great post as always. I am wondering -- does this imply that all of the SaaS companies that round-tripped up to 50x ARR and back down to <10x are "overstating" SBC expense since in most cases they did the bulk of their hiring in ~2021 at peak stock prices? Put another way, isn't almost every public SaaS company (at least the growthier ones) a "Company 1" rather than a "Company 2", right now at least?