The Dilution Reckoning | Time to Fix Stock-Based Comp

CFOs need to re-evaluate acceptable dilution levels in 2026. The math has changed.

Today’s Sponsor: Deel

Payroll is entering a new era with AI-driven compliance, real-time visibility, and higher expectations from the board.

Deel’s Payroll Strategy Toolkit gives finance leaders a step-by-step roadmap to modernize payroll, reduce manual risk, and build a scalable strategy with confidence.

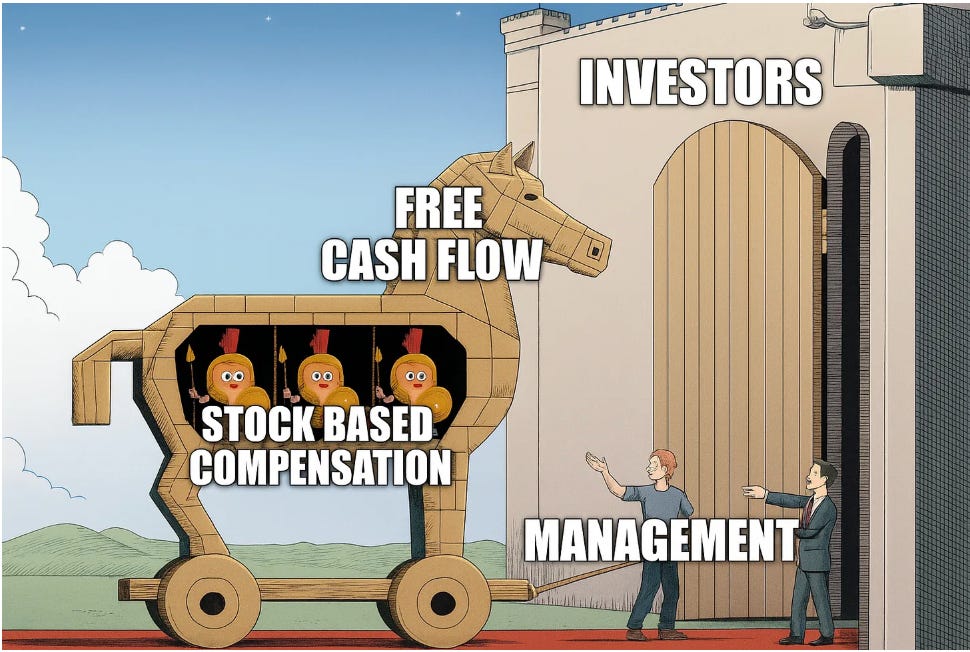

The SBC Trojan Horse

Stock-based compensation (SBC) is a sneaky destroyer of shareholder returns and it is going to punch a lot of tech companies in the face as growth slows.

We see this destruction show up in shareholder dilution. Tech companies have typically had high relative dilution. Investors accepted that high dilution though because of the promise of exponential valuation growth. But those expectations and the math have changed in 2026…

How do you increase company valuation?

While valuations can be volatile (as we are seeing today in the SaaS market), long-term valuations are determined by a company’s ability to improve free cash flow per share. In the short term, they are volatile as investors digest how events (disruption from AI) may impact long-term FCF/share potential.

There are two primary ways to improve FCF/share.

Increase FCF

Grow revenue

Cut costs

Reduce dilution (fewer shares in the denominator)

Today’s post is focused on the harsh reality of dilution that many software companies are facing in 2026.

What is the right level of dilution?

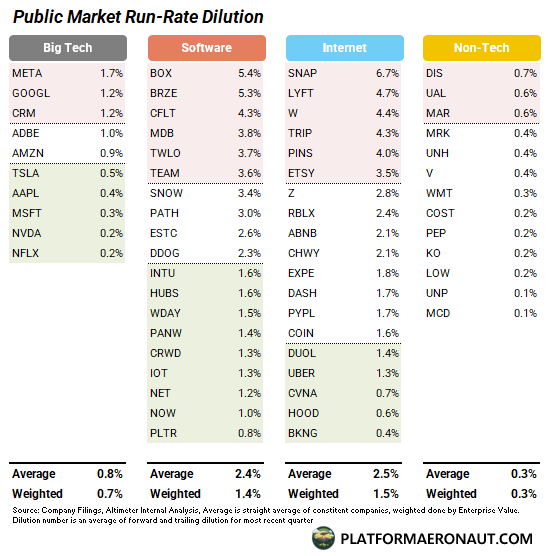

Many people default to “What is the standard dilution for our company size or industry?” Below is a great breakdown of high dilution (red), average dilution (white), and good dilution (green) segmented by company type. It’s really interesting to see how different dilution rates can be across these segments.

Notice I don’t say “bad”, “good”, or “best” dilution…more on this below.

The above data is an interesting starting point, but it doesn’t answer the question of how much dilution is acceptable. Like all benchmarking…context is important.

All else being equal, we obviously want lower dilution. But investors accept higher dilution if it creates an even more valuable company. Remember, valuations increase when FCF per share increases. If we are increasing the “share” by adding dilution, then we must justify it with an even higher company lifetime FCF creation.

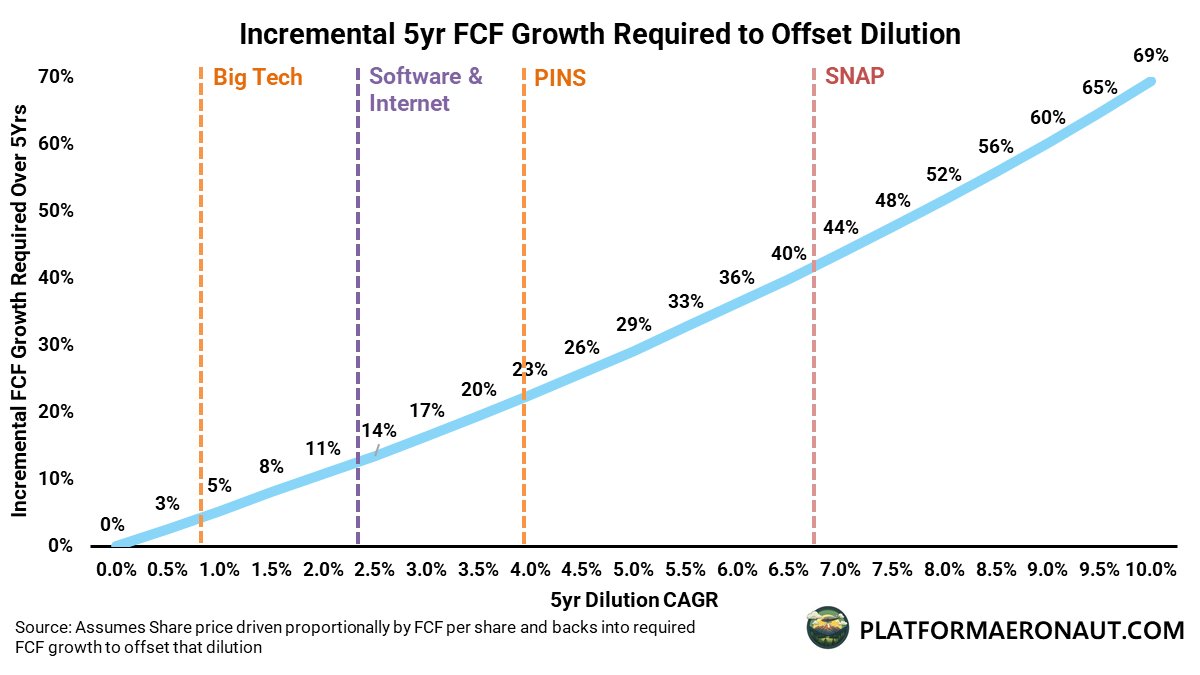

Thomas Reiner’s chart below is the clearest illustration I have seen to show this point.

Snap (social media app) would have to grow FCF/share by ~42% over 5 years to simply offset their massive shareholder dilution. And software companies would have to grow FCF/share by 13% to offset their average 2.4% dilution.

This is why high-growth companies can justify high dilution rates. They are compensating employees and getting the top talent needed to grow the company’s valuation even faster (hopefully much faster).

As revenue growth falls, companies are slow to adjust dilution rates. The acceptable dilution rate while you are growing 75%+ is going to look very different than when you are only growing <25%. Everyone talks about improving FCF margins when revenue growth slows (Rule of 40 Score), but dilution is rarely discussed (especially private companies).

How to Fix Your Dilution Problem

While every company’s dream is to fix the dilution problem through even higher revenue growth, that is much harder for most companies today. So it needs to come from the other two options: 1) cutting costs to improve FCF and/or 2) less dilution.

Unfortunately, both of these are probably going to be solved by the same thing: Layoffs.

Layoffs hit two birds with one stone: 1) FCF is higher because you cut payroll costs and 2) dilution is lower because there is less employee stock-based comp.

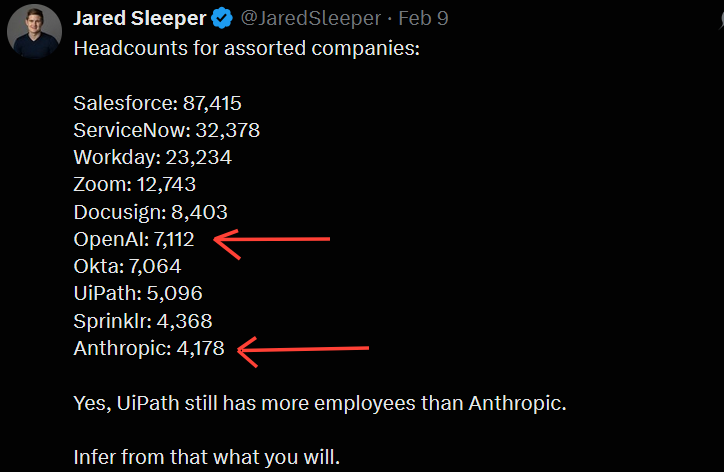

If you look at the headcount of some of these software companies, you can quickly see the potential impact layoffs could have. In an AI world, many of these companies could probably operate at close to 50% of current headcount levels…

Ideally, companies just freeze hiring and then revenue growth will work its way through so layoffs aren’t necessary. But if revenue growth is slow and AI can make things much more efficient, then companies can’t afford to wait.

Here is what exec teams are actively discussing in 2026 to fix their dilution problem:

Hiring freeze - no new hires and all backfills must be justified

Offshoring - cost of offshoring by country

Most folks think about the lower cash comp when offshoring, but equity expectations are typically much lower in other countries, so dilution decreases even more relative to cash comp.

Layoffs

Reduce equity grants - below are a few things folks are doing:

I am seeing a lot of companies move from 75th percentile to 50th (or below) for equity grants

Reduce/eliminate annual performance grants (Zoom recently did this)

Hire less senior folks. Cash comp may go up ~5x from entry level to executive, but equity comp increases 1,000x+

Final Thoughts

Stock-based comp (and the dilution from it) is a necessary tool to build the right team in order to expand the value of the company. If you manage it poorly, then you will lose more company value than you gain from lower dilution. Be careful…

Many of you have experienced a sudden change in revenue growth rates. Don’t just focus on your Rule of 40 Score and manage FCF. You must think about how you will adjust dilution as well.

Footnotes:

Great read: Payroll Strategy Toolkit. My friends (and today’s sponsor :) at Deel wrote the playbook for how payroll should work in 2026.

Want to Sponsor? I am opening up the rest of the year now so email me at onlycfo@onlycfo.io to have your wildest marketing dreams come true.

Bonus Content: Explaining Dilution To Your Grandma

Who Stole My Pizza?

Think of a company’s valuation as a pizza cut into 8 slices.

Founders: 2 slices

VCs: 5 slices

Employees: 1 slice

Now you hire a big executive and grant them equity equal to 1 slice of pizza. If the pizza stays the same size, everyone’s slice gets slightly smaller. You can’t magically create a ninth slice without shrinking everyone else’s.

That’s dilution’s ugly impact.

I do this all the time to my kids when their friends come over. “Sorry, but you have to share pizza with all your friends”. Everyone gets less pizza.

But companies are not “giving away” pizza. It’s compensation to help bake a bigger pizza (hopefully a lot bigger). So even if we cut more slices, the entire pizza is bigger. Even though your slice is smaller, you still get more pizza.

The bigger the slice you give employees, the higher the expectation that they’ll bake a much bigger pizza.

*May all your employees bake you lots of pizza

One thing I'd add: dilution should be measured against expectations already baked into the stock price, not just FCF growth in a vacuum. The base rate of companies that consistently beat what's already priced in is pretty low, which makes the math even harder than it looks.

Love the point about adjusting dilution as growth slows. Worth noting that value creation per employee follows a power law, but most equity programs hand out grants in fairly uniform bands by level. Better alignment with actual contribution would stretch each dilution dollar a lot further.

And a simple habit that pays off: track net share count over rolling three to five year windows. The gap between gross and net buyback yield shows you the real cost of SBC. It's almost always bigger than the headline suggests.

Always appreciate your POV. I’d genuinely love to see you write an opposite take, too:

The prevailing narrative is AI = 30–50% fewer employees + more offshoring. But I’d love to see the CFO thought experiment for a world where keeping and upgrading full-time onshore teams is actually the move. What would have to change?

And if the answer is that the current financial models & shareholder laws simply can’t justify that outcome, then maybe the more interesting question is whether the models + laws themselves need to be rethought.

A slightly crazy, **out-of-the-box** take on that would be a great read.